The Concepts section helps you learn about the parts of the Kubernetes system and the abstractions Kubernetes uses to represent your cluster, and helps you obtain a deeper understanding of how Kubernetes works.

This is the multi-page printable view of this section. Click here to print.

Concepts

- 1: Overview

- 1.1: Kubernetes Components

- 1.2: Objects In Kubernetes

- 1.2.1: Kubernetes Object Management

- 1.2.2: Object Names and IDs

- 1.2.3: Labels and Selectors

- 1.2.4: Namespaces

- 1.2.5: Annotations

- 1.2.6: Field Selectors

- 1.2.7: Finalizers

- 1.2.8: Owners and Dependents

- 1.2.9: Recommended Labels

- 1.2.10: Storage Versions

- 1.3: The Kubernetes API

- 2: Cluster Architecture

- 2.1: Nodes

- 2.2: Communication between Nodes and the Control Plane

- 2.3: Controllers

- 2.4: Leases

- 2.5: Cloud Controller Manager

- 2.6: About cgroup v2

- 2.7: Kubernetes Self-Healing

- 2.8: Garbage Collection

- 2.9: Mixed Version Proxy

- 3: Containers

- 3.1: Images

- 3.2: Container Environment

- 3.3: Runtime Class

- 3.4: Container Lifecycle Hooks

- 3.5: Container Runtime Interface (CRI)

- 4: Workloads

- 4.1: Pods

- 4.1.1: Pod Lifecycle

- 4.1.2: Init Containers

- 4.1.3: Sidecar Containers

- 4.1.4: Ephemeral Containers

- 4.1.5: Disruptions

- 4.1.6: Pod Hostname

- 4.1.7: Pod Quality of Service Classes

- 4.1.8: Workload Reference

- 4.1.9: User Namespaces

- 4.1.10: Downward API

- 4.1.11: Advanced Pod Configuration

- 4.2: Workload API

- 4.2.1: Pod Group Policies

- 4.3: Workload Management

- 4.3.1: Deployments

- 4.3.2: ReplicaSet

- 4.3.3: StatefulSets

- 4.3.4: DaemonSet

- 4.3.5: Jobs

- 4.3.6: Automatic Cleanup for Finished Jobs

- 4.3.7: CronJob

- 4.3.8: ReplicationController

- 4.4: Managing Workloads

- 4.5: Autoscaling Workloads

- 4.6: Horizontal Pod Autoscaling

- 4.7: Vertical Pod Autoscaling

- 5: Services, Load Balancing, and Networking

- 5.1: Service

- 5.2: Ingress

- 5.3: Ingress Controllers

- 5.4: Gateway API

- 5.5: EndpointSlices

- 5.6: Network Policies

- 5.7: DNS for Services and Pods

- 5.8: IPv4/IPv6 dual-stack

- 5.9: Topology Aware Routing

- 5.10: Networking on Windows

- 5.11: Service ClusterIP allocation

- 5.12: Service Internal Traffic Policy

- 6: Storage

- 6.1: Volumes

- 6.2: Persistent Volumes

- 6.3: Projected Volumes

- 6.4: Ephemeral Volumes

- 6.5: Storage Classes

- 6.6: Volume Attributes Classes

- 6.7: Dynamic Volume Provisioning

- 6.8: Volume Snapshots

- 6.9: Volume Snapshot Classes

- 6.10: CSI Volume Cloning

- 6.11: Storage Capacity

- 6.12: Node-specific Volume Limits

- 6.13: Local ephemeral storage

- 6.14: Volume Health Monitoring

- 6.15: Windows Storage

- 7: Configuration

- 7.1: ConfigMaps

- 7.2: Secrets

- 7.3: Liveness, Readiness, and Startup Probes

- 7.4: Resource Management for Pods and Containers

- 7.5: Organizing Cluster Access Using kubeconfig Files

- 7.6: Resource Management for Windows nodes

- 8: Security

- 8.1: Cloud Native Security and Kubernetes

- 8.2: Pod Security Standards

- 8.3: Pod Security Admission

- 8.4: Service Accounts

- 8.5: Pod Security Policies

- 8.6: Security For Linux Nodes

- 8.7: Security For Windows Nodes

- 8.8: Controlling Access to the Kubernetes API

- 8.9: Role Based Access Control Good Practices

- 8.10: Good practices for Kubernetes Secrets

- 8.11: Multi-tenancy

- 8.12: Hardening Guide - Authentication Mechanisms

- 8.13: Hardening Guide - Scheduler Configuration

- 8.14: Kubernetes API Server Bypass Risks

- 8.15: Linux kernel security constraints for Pods and containers

- 8.16: Security Checklist

- 8.17: Application Security Checklist

- 9: Policies

- 9.1: Limit Ranges

- 9.2: Resource Quotas

- 9.3: Process ID Limits And Reservations

- 9.4: Node Resource Managers

- 10: Scheduling, Preemption and Eviction

- 10.1: Kubernetes Scheduler

- 10.2: Assigning Pods to Nodes

- 10.3: Pod Overhead

- 10.4: Pod Scheduling Readiness

- 10.5: Pod Topology Spread Constraints

- 10.6: Taints and Tolerations

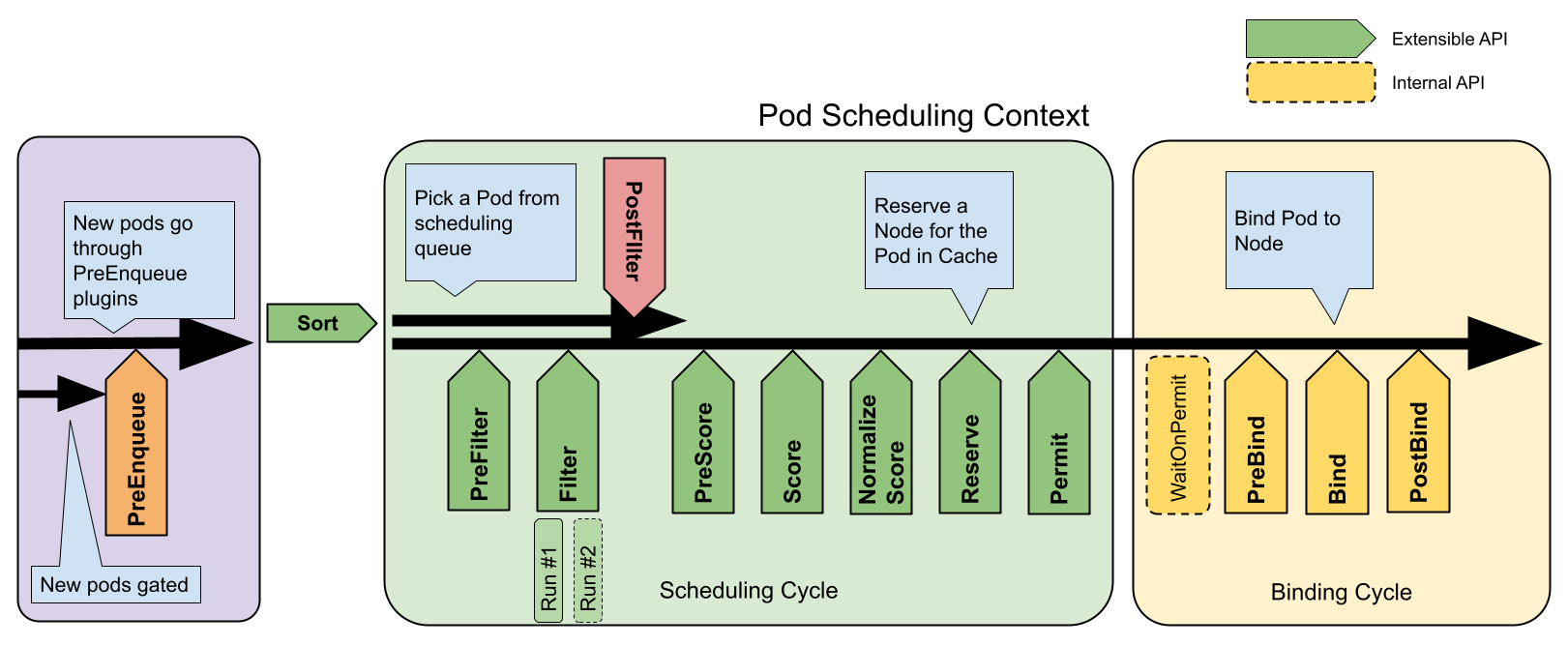

- 10.7: Scheduling Framework

- 10.8: Dynamic Resource Allocation

- 10.9: Gang Scheduling

- 10.10: Scheduler Performance Tuning

- 10.11: Resource Bin Packing

- 10.12: Pod Priority and Preemption

- 10.13: Node-pressure Eviction

- 10.14: API-initiated Eviction

- 10.15: Node Declared Features

- 11: Cluster Administration

- 11.1: Node Shutdowns

- 11.2: Swap memory management

- 11.3: Node Autoscaling

- 11.4: Certificates

- 11.5: Cluster Networking

- 11.6: Observability

- 11.7: Admission Webhook Good Practices

- 11.8: Good practices for Dynamic Resource Allocation as a Cluster Admin

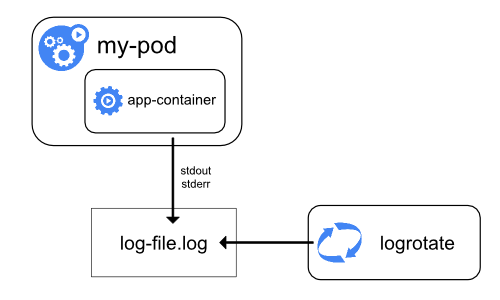

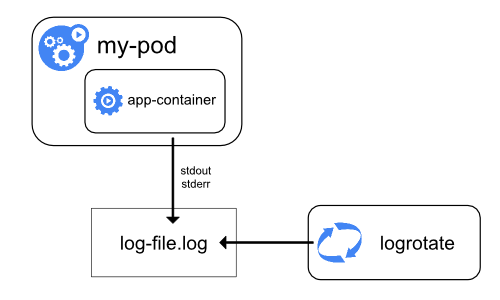

- 11.9: Logging Architecture

- 11.10: Compatibility Version For Kubernetes Control Plane Components

- 11.11: Metrics For Kubernetes System Components

- 11.12: Metrics for Kubernetes Object States

- 11.13: System Logs

- 11.14: Traces For Kubernetes System Components

- 11.15: Proxies in Kubernetes

- 11.16: API Priority and Fairness

- 11.17: Installing Addons

- 11.18: Coordinated Leader Election

- 12: Windows in Kubernetes

- 13: Extending Kubernetes

- 13.1: Compute, Storage, and Networking Extensions

- 13.1.1: Network Plugins

- 13.1.2: Device Plugins

- 13.2: Extending the Kubernetes API

- 13.2.1: Custom Resources

- 13.2.2: Kubernetes API Aggregation Layer

- 13.3: Operator pattern

1 - Overview

This page is an overview of Kubernetes.

The name Kubernetes originates from Greek, meaning helmsman or pilot. K8s as an abbreviation results from counting the eight letters between the "K" and the "s". Google open sourced the Kubernetes project in 2014. Kubernetes combines over 15 years of Google's experience running production workloads at scale with best-of-breed ideas and practices from the community.

Why you need Kubernetes and what it can do

Containers are a good way to bundle and run your applications. In a production environment, you need to manage the containers that run the applications and ensure that there is no downtime. For example, if a container goes down, another container needs to start. Wouldn't it be easier if this behavior was handled by a system?

That's how Kubernetes comes to the rescue! Kubernetes provides you with a framework to run distributed systems resiliently. It takes care of scaling and failover for your application, provides deployment patterns, and more. For example: Kubernetes can easily manage a canary deployment for your system.

Kubernetes provides you with:

- Service discovery and load balancing Kubernetes can expose a container using a DNS name or its own IP address. If traffic to a container is high, Kubernetes is able to load balance and distribute the network traffic so that the deployment is stable.

- Storage orchestration Kubernetes allows you to automatically mount a storage system of your choice, such as local storage, public cloud providers, and more.

- Automated rollouts and rollbacks You can describe the desired state for your deployed containers using Kubernetes, and it can change the actual state to the desired state at a controlled rate. For example, you can automate Kubernetes to create new containers for your deployment, remove existing containers and adopt all their resources to the new container.

- Automatic bin packing You provide Kubernetes with a cluster of nodes that it can use to run containerized tasks. You tell Kubernetes how much CPU and memory (RAM) each container needs. Kubernetes can fit containers onto your nodes to make the best use of your resources.

- Self-healing Kubernetes restarts containers that fail, replaces containers, kills containers that don't respond to your user-defined health check, and doesn't advertise them to clients until they are ready to serve.

- Secret and configuration management Kubernetes lets you store and manage sensitive information, such as passwords, OAuth tokens, and SSH keys. You can deploy and update secrets and application configuration without rebuilding your container images, and without exposing secrets in your stack configuration.

- Batch execution In addition to services, Kubernetes can manage your batch and CI workloads, replacing containers that fail, if desired.

- Horizontal scaling Scale your application up and down with a simple command, with a UI, or automatically based on CPU usage.

- IPv4/IPv6 dual-stack Allocation of IPv4 and IPv6 addresses to Pods and Services

- Designed for extensibility Add features to your Kubernetes cluster without changing upstream source code.

What Kubernetes is not

Kubernetes is not a traditional, all-inclusive PaaS (Platform as a Service) system. Since Kubernetes operates at the container level rather than at the hardware level, it provides some generally applicable features common to PaaS offerings, such as deployment, scaling, load balancing, and lets users integrate their logging, monitoring, and alerting solutions. However, Kubernetes is not monolithic, and these default solutions are optional and pluggable. Kubernetes provides the building blocks for building developer platforms, but preserves user choice and flexibility where it is important.

Kubernetes:

- Does not limit the types of applications supported. Kubernetes aims to support an extremely diverse variety of workloads, including stateless, stateful, and data-processing workloads. If an application can run in a container, it should run great on Kubernetes.

- Does not deploy source code and does not build your application. Continuous Integration, Delivery, and Deployment (CI/CD) workflows are determined by organization cultures and preferences as well as technical requirements.

- Does not provide application-level services, such as middleware (for example, message buses), data-processing frameworks (for example, Spark), databases (for example, MySQL), caches, nor cluster storage systems (for example, Ceph) as built-in services. Such components can run on Kubernetes, and/or can be accessed by applications running on Kubernetes through portable mechanisms, such as the Open Service Broker.

- Does not dictate logging, monitoring, or alerting solutions. It provides some integrations as proof of concept, and mechanisms to collect and export metrics.

- Does not provide nor mandate a configuration language/system (for example, Jsonnet). It provides a declarative API that may be targeted by arbitrary forms of declarative specifications.

- Does not provide nor adopt any comprehensive machine configuration, maintenance, management, or self-healing systems.

- Additionally, Kubernetes is not a mere orchestration system. In fact, it eliminates the need for orchestration. The technical definition of orchestration is execution of a defined workflow: first do A, then B, then C. In contrast, Kubernetes comprises a set of independent, composable control processes that continuously drive the current state towards the provided desired state. It shouldn't matter how you get from A to C. Centralized control is also not required. This results in a system that is easier to use and more powerful, robust, resilient, and extensible.

Historical context for Kubernetes

Let's take a look at why Kubernetes is so useful by going back in time.

Traditional deployment era:

Early on, organizations ran applications on physical servers. There was no way to define resource boundaries for applications in a physical server, and this caused resource allocation issues. For example, if multiple applications run on a physical server, there can be instances where one application would take up most of the resources, and as a result, the other applications would underperform. A solution for this would be to run each application on a different physical server. But this did not scale as resources were underutilized, and it was expensive for organizations to maintain many physical servers.

Virtualized deployment era:

As a solution, virtualization was introduced. It allows you to run multiple Virtual Machines (VMs) on a single physical server's CPU. Virtualization allows applications to be isolated between VMs and provides a level of security as the information of one application cannot be freely accessed by another application.

Virtualization allows better utilization of resources in a physical server and allows better scalability because an application can be added or updated easily, reduces hardware costs, and much more. With virtualization you can present a set of physical resources as a cluster of disposable virtual machines.

Each VM is a full machine running all the components, including its own operating system, on top of the virtualized hardware.

Container deployment era:

Containers are similar to VMs, but they have relaxed isolation properties to share the Operating System (OS) among the applications. Therefore, containers are considered lightweight. Similar to a VM, a container has its own filesystem, share of CPU, memory, process space, and more. As they are decoupled from the underlying infrastructure, they are portable across clouds and OS distributions.

Containers have become popular because they provide extra benefits, such as:

- Agile application creation and deployment: increased ease and efficiency of container image creation compared to VM image use.

- Continuous development, integration, and deployment: provides reliable and frequent container image build and deployment with quick and efficient rollbacks (due to image immutability).

- Dev and Ops separation of concerns: create application container images at build/release time rather than deployment time, thereby decoupling applications from infrastructure.

- Observability: not only surfaces OS-level information and metrics, but also application health and other signals.

- Environmental consistency across development, testing, and production: runs the same on a laptop as it does in the cloud.

- Cloud and OS distribution portability: runs on Ubuntu, RHEL, CoreOS, on-premises, on major public clouds, and anywhere else.

- Application-centric management: raises the level of abstraction from running an OS on virtual hardware to running an application on an OS using logical resources.

- Loosely coupled, distributed, elastic, liberated micro-services: applications are broken into smaller, independent pieces and can be deployed and managed dynamically – not a monolithic stack running on one big single-purpose machine.

- Resource isolation: predictable application performance.

- Resource utilization: high efficiency and density.

What's next

- Take a look at the Kubernetes Components

- Take a look at the The Kubernetes API

- Take a look at the Cluster Architecture

- Ready to Get Started?

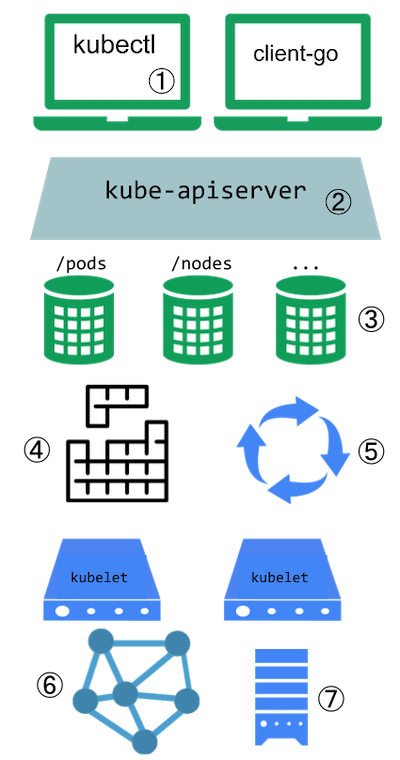

1.1 - Kubernetes Components

This page provides a high-level overview of the essential components that make up a Kubernetes cluster.

The components of a Kubernetes cluster

Core Components

A Kubernetes cluster consists of a control plane and one or more worker nodes. Here's a brief overview of the main components:

Control Plane Components

Manage the overall state of the cluster:

- kube-apiserver

- The core component server that exposes the Kubernetes HTTP API.

- etcd

- Consistent and highly-available key value store for all API server data.

- kube-scheduler

- Looks for Pods not yet bound to a node, and assigns each Pod to a suitable node.

- kube-controller-manager

- Runs controllers to implement Kubernetes API behavior.

- cloud-controller-manager (optional)

- Integrates with underlying cloud provider(s).

Node Components

Run on every node, maintaining running pods and providing the Kubernetes runtime environment:

- kubelet

- Ensures that Pods are running, including their containers.

- kube-proxy (optional)

- Maintains network rules on nodes to implement Services.

- Container runtime

- Software responsible for running containers. Read Container Runtimes to learn more.

Your cluster may require additional software on each node; for example, you might also run systemd on a Linux node to supervise local components.

Addons

Addons extend the functionality of Kubernetes. A few important examples include:

- DNS

- For cluster-wide DNS resolution.

- Web UI (Dashboard)

- For cluster management via a web interface.

- Container Resource Monitoring

- For collecting and storing container metrics.

- Cluster-level Logging

- For saving container logs to a central log store.

Flexibility in Architecture

Kubernetes allows for flexibility in how these components are deployed and managed. The architecture can be adapted to various needs, from small development environments to large-scale production deployments.

For more detailed information about each component and various ways to configure your cluster architecture, see the Cluster Architecture page.

1.2 - Objects In Kubernetes

This page explains how Kubernetes objects are represented in the Kubernetes API, and how you can

express them in .yaml format.

Understanding Kubernetes objects

Kubernetes objects are persistent entities in the Kubernetes system. Kubernetes uses these entities to represent the state of your cluster. Specifically, they can describe:

- What containerized applications are running (and on which nodes)

- The resources available to those applications

- The policies around how those applications behave, such as restart policies, upgrades, and fault-tolerance

A Kubernetes object is a "record of intent"--once you create the object, the Kubernetes system will constantly work to ensure that the object exists. By creating an object, you're effectively telling the Kubernetes system what you want your cluster's workload to look like; this is your cluster's desired state.

To work with Kubernetes objects—whether to create, modify, or delete them—you'll need to use the

Kubernetes API. When you use the kubectl command-line

interface, for example, the CLI makes the necessary Kubernetes API calls for you. You can also use

the Kubernetes API directly in your own programs using one of the

Client Libraries.

Object spec and status

Almost every Kubernetes object includes two nested object fields that govern

the object's configuration: the object spec and the object status.

For objects that have a spec, you have to set this when you create the object,

providing a description of the characteristics you want the resource to have:

its desired state.

The status describes the current state of the object, supplied and updated

by the Kubernetes system and its components. The Kubernetes

control plane continually

and actively manages every object's actual state to match the desired state you

supplied.

For example: in Kubernetes, a Deployment is an object that can represent an

application running on your cluster. When you create the Deployment, you

might set the Deployment spec to specify that you want three replicas of

the application to be running. The Kubernetes system reads the Deployment

spec and starts three instances of your desired application--updating

the status to match your spec. If any of those instances should fail

(a status change), the Kubernetes system responds to the difference

between spec and status by making a correction--in this case, starting

a replacement instance.

For more information on the object spec, status, and metadata, see the Kubernetes API Conventions.

Describing a Kubernetes object

When you create an object in Kubernetes, you must provide the object spec that describes its

desired state, as well as some basic information about the object (such as a name). When you use

the Kubernetes API to create the object (either directly or via kubectl), that API request must

include that information as JSON in the request body.

Most often, you provide the information to kubectl in a file known as a manifest.

By convention, manifests are YAML (you could also use JSON format).

Tools such as kubectl convert the information from a manifest into JSON or another supported

serialization format when making the API request over HTTP.

Here's an example manifest that shows the required fields and object spec for a Kubernetes Deployment:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: nginx-deployment

spec:

selector:

matchLabels:

app: nginx

replicas: 2 # tells deployment to run 2 pods matching the template

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: nginx

spec:

containers:

- name: nginx

image: nginx:1.14.2

ports:

- containerPort: 80

One way to create a Deployment using a manifest file like the one above is to use the

kubectl apply command

in the kubectl command-line interface, passing the .yaml file as an argument. Here's an example:

kubectl apply -f https://k8s.io/examples/application/deployment.yaml

The output is similar to this:

deployment.apps/nginx-deployment created

Required fields

In the manifest (YAML or JSON file) for the Kubernetes object you want to create, you'll need to set values for the following fields:

apiVersion- Which version of the Kubernetes API you're using to create this objectkind- What kind of object you want to createmetadata- Data that helps uniquely identify the object, including anamestring,UID, and optionalnamespacespec- What state you desire for the object

The precise format of the object spec is different for every Kubernetes object, and contains

nested fields specific to that object. The Kubernetes API Reference

can help you find the spec format for all of the objects you can create using Kubernetes.

For example, see the spec field

for the Pod API reference.

For each Pod, the .spec field specifies the pod and its desired state (such as the container image name for

each container within that pod).

Another example of an object specification is the

spec field

for the StatefulSet API. For StatefulSet, the .spec field specifies the StatefulSet and

its desired state.

Within the .spec of a StatefulSet is a template

for Pod objects. That template describes Pods that the StatefulSet controller will create in order to

satisfy the StatefulSet specification.

Different kinds of objects can also have different .status; again, the API reference pages

detail the structure of that .status field, and its content for each different type of object.

See Kubernetes Configuration Best Practices for additional information on writing YAML configuration files.

Server side field validation

Starting with Kubernetes v1.25, the API server offers server side

field validation

that detects unrecognized or duplicate fields in an object. It provides all the functionality

of kubectl --validate on the server side.

The kubectl tool uses the --validate flag to set the level of field validation. It accepts the

values ignore, warn, and strict while also accepting the values true (equivalent to strict)

and false (equivalent to ignore). The default validation setting for kubectl is --validate=true.

Strict- Strict field validation, errors on validation failure

Warn- Field validation is performed, but errors are exposed as warnings rather than failing the request

Ignore- No server side field validation is performed

When kubectl cannot connect to an API server that supports field validation it will fall back

to using client-side validation. Kubernetes 1.27 and later versions always offer field validation;

older Kubernetes releases might not. If your cluster is older than v1.27, check the documentation

for your version of Kubernetes.

What's next

If you're new to Kubernetes, read more about the following:

- Pods which are the most important basic Kubernetes objects.

- Deployment objects.

- Controllers in Kubernetes.

- kubectl and kubectl commands.

Kubernetes Object Management

explains how to use kubectl to manage objects.

You might need to install kubectl if you don't already have it available.

To learn about the Kubernetes API in general, visit:

To learn about objects in Kubernetes in more depth, read other pages in this section:

1.2.1 - Kubernetes Object Management

The kubectl command-line tool supports several different ways to create and manage

Kubernetes objects. This document provides an overview of the different

approaches. Read the Kubectl book for

details of managing objects by Kubectl.

Management techniques

Warning:

A Kubernetes object should be managed using only one technique. Mixing and matching techniques for the same object results in undefined behavior.| Management technique | Operates on | Recommended environment | Supported writers | Learning curve |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imperative commands | Live objects | Development projects | 1+ | Lowest |

| Imperative object configuration | Individual files | Production projects | 1 | Moderate |

| Declarative object configuration | Directories of files | Production projects | 1+ | Highest |

Imperative commands

When using imperative commands, a user operates directly on live objects

in a cluster. The user provides operations to

the kubectl command as arguments or flags.

This is the recommended way to get started or to run a one-off task in a cluster. Because this technique operates directly on live objects, it provides no history of previous configurations.

Examples

Run an instance of the nginx container by creating a Deployment object:

kubectl create deployment nginx --image nginx

Trade-offs

Advantages compared to object configuration:

- Commands are expressed as a single action word.

- Commands require only a single step to make changes to the cluster.

Disadvantages compared to object configuration:

- Commands do not integrate with change review processes.

- Commands do not provide an audit trail associated with changes.

- Commands do not provide a source of records except for what is live.

- Commands do not provide a template for creating new objects.

Imperative object configuration

In imperative object configuration, the kubectl command specifies the operation (create, replace, etc.), optional flags and at least one file name. The file specified must contain a full definition of the object in YAML or JSON format.

See the API reference for more details on object definitions.

Warning:

The imperativereplace command replaces the existing

spec with the newly provided one, dropping all changes to the object missing from

the configuration file. This approach should not be used with resource

types whose specs are updated independently of the configuration file.

Services of type LoadBalancer, for example, have their externalIPs field updated

independently from the configuration by the cluster.Examples

Create the objects defined in a configuration file:

kubectl create -f nginx.yaml

Delete the objects defined in two configuration files:

kubectl delete -f nginx.yaml -f redis.yaml

Update the objects defined in a configuration file by overwriting the live configuration:

kubectl replace -f nginx.yaml

Trade-offs

Advantages compared to imperative commands:

- Object configuration can be stored in a source control system such as Git.

- Object configuration can integrate with processes such as reviewing changes before push and audit trails.

- Object configuration provides a template for creating new objects.

Disadvantages compared to imperative commands:

- Object configuration requires basic understanding of the object schema.

- Object configuration requires the additional step of writing a YAML file.

Advantages compared to declarative object configuration:

- Imperative object configuration behavior is simpler and easier to understand.

- As of Kubernetes version 1.5, imperative object configuration is more mature.

Disadvantages compared to declarative object configuration:

- Imperative object configuration works best on files, not directories.

- Updates to live objects must be reflected in configuration files, or they will be lost during the next replacement.

Declarative object configuration

When using declarative object configuration, a user operates on object

configuration files stored locally, however the user does not define the

operations to be taken on the files. Create, update, and delete operations

are automatically detected per-object by kubectl. This enables working on

directories, where different operations might be needed for different objects.

Note:

Declarative object configuration retains changes made by other writers, even if the changes are not merged back to the object configuration file. This is possible by using thepatch API operation to write only

observed differences, instead of using the replace

API operation to replace the entire object configuration.Examples

Process all object configuration files in the configs directory, and create or

patch the live objects. You can first diff to see what changes are going to be

made, and then apply:

kubectl diff -f configs/

kubectl apply -f configs/

Recursively process directories:

kubectl diff -R -f configs/

kubectl apply -R -f configs/

Trade-offs

Advantages compared to imperative object configuration:

- Changes made directly to live objects are retained, even if they are not merged back into the configuration files.

- Declarative object configuration has better support for operating on directories and automatically detecting operation types (create, patch, delete) per-object.

Disadvantages compared to imperative object configuration:

- Declarative object configuration is harder to debug and understand results when they are unexpected.

- Partial updates using diffs create complex merge and patch operations.

What's next

- Managing Kubernetes Objects Using Imperative Commands

- Imperative Management of Kubernetes Objects Using Configuration Files

- Declarative Management of Kubernetes Objects Using Configuration Files

- Declarative Management of Kubernetes Objects Using Kustomize

- Kubectl Command Reference

- Kubectl Book

- Kubernetes API Reference

1.2.2 - Object Names and IDs

Each object in your cluster has a Name that is unique for that type of resource. Every Kubernetes object also has a UID that is unique across your whole cluster.

For example, you can only have one Pod named myapp-1234 within the same namespace, but you can have one Pod and one Deployment that are each named myapp-1234.

For non-unique user-provided attributes, Kubernetes provides labels and annotations.

Names

A client-provided string that refers to an object in a resource

URL, such as /api/v1/pods/some-name.

Only one object of a given kind can have a given name at a time. However, if you delete the object, you can make a new object with the same name.

Names must be unique across all API versions of the same resource. API resources are distinguished by their API group, resource type, namespace (for namespaced resources), and name. In other words, API version is irrelevant in this context.

Note:

In cases when objects represent a physical entity, like a Node representing a physical host, when the host is re-created under the same name without deleting and re-creating the Node, Kubernetes treats the new host as the old one, which may lead to inconsistencies.The server may generate a name when generateName is provided instead of name in a resource create request.

When generateName is used, the provided value is used as a name prefix, which server appends a generated suffix

to. Even though the name is generated, it may conflict with existing names resulting in an HTTP 409 response. This

became far less likely to happen in Kubernetes v1.31 and later, since the server will make up to 8 attempts to generate a

unique name before returning an HTTP 409 response.

Below are four types of commonly used name constraints for resources.

DNS Subdomain Names

Most resource types require a name that can be used as a DNS subdomain name as defined in RFC 1123. This means the name must:

- contain no more than 253 characters

- contain only lowercase alphanumeric characters, '-' or '.'

- start with an alphanumeric character

- end with an alphanumeric character

RFC 1123 Label Names

Some resource types require their names to follow the DNS label standard as defined in RFC 1123. This means the name must:

- contain at most 63 characters

- contain only lowercase alphanumeric characters or '-'

- start with an alphabetic character

- end with an alphanumeric character

Note:

When theRelaxedServiceNameValidation feature gate is enabled,

Service object names are allowed to start with a digit.RFC 1035 Label Names

Some resource types require their names to follow the DNS label standard as defined in RFC 1035. This means the name must:

- contain at most 63 characters

- contain only lowercase alphanumeric characters or '-'

- start with an alphabetic character

- end with an alphanumeric character

Note:

While RFC 1123 technically allows labels to start with digits, the current Kubernetes implementation requires both RFC 1035 and RFC 1123 labels to start with an alphabetic character. The exception is when theRelaxedServiceNameValidation

feature gate is enabled for Service objects, which allows Service names to start with digits.Path Segment Names

Some resource types require their names to be able to be safely encoded as a path segment. In other words, the name may not be "." or ".." and the name may not contain "/" or "%".

Here's an example manifest for a Pod named nginx-demo.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: nginx-demo

spec:

containers:

- name: nginx

image: nginx:1.14.2

ports:

- containerPort: 80

Note:

Some resource types have additional restrictions on their names.UIDs

A Kubernetes systems-generated string to uniquely identify objects.

Every object created over the whole lifetime of a Kubernetes cluster has a distinct UID. It is intended to distinguish between historical occurrences of similar entities.

Kubernetes UIDs are universally unique identifiers (also known as UUIDs). UUIDs are standardized as ISO/IEC 9834-8 and as ITU-T X.667.

What's next

- Read about labels and annotations in Kubernetes.

- See the Identifiers and Names in Kubernetes design document.

1.2.3 - Labels and Selectors

Labels are key/value pairs that are attached to objects such as Pods. Labels are intended to be used to specify identifying attributes of objects that are meaningful and relevant to users, but do not directly imply semantics to the core system. Labels can be used to organize and to select subsets of objects. Labels can be attached to objects at creation time and subsequently added and modified at any time. Each object can have a set of key/value labels defined. Each Key must be unique for a given object.

"metadata": {

"labels": {

"key1" : "value1",

"key2" : "value2"

}

}

Labels allow for efficient queries and watches and are ideal for use in UIs and CLIs. Non-identifying information should be recorded using annotations.

Motivation

Labels enable users to map their own organizational structures onto system objects in a loosely coupled fashion, without requiring clients to store these mappings.

Service deployments and batch processing pipelines are often multi-dimensional entities (e.g., multiple partitions or deployments, multiple release tracks, multiple tiers, multiple micro-services per tier). Management often requires cross-cutting operations, which breaks encapsulation of strictly hierarchical representations, especially rigid hierarchies determined by the infrastructure rather than by users.

Example labels:

"release" : "stable","release" : "canary""environment" : "dev","environment" : "qa","environment" : "production""tier" : "frontend","tier" : "backend","tier" : "cache""partition" : "customerA","partition" : "customerB""track" : "daily","track" : "weekly"

These are examples of commonly used labels; you are free to develop your own conventions. Keep in mind that label Key must be unique for a given object.

Syntax and character set

Labels are key/value pairs. Valid label keys have two segments: an optional

prefix and name, separated by a slash (/). The name segment is required and

must be 63 characters or less, beginning and ending with an alphanumeric

character ([a-z0-9A-Z]) with dashes (-), underscores (_), dots (.),

and alphanumerics between. The prefix is optional. If specified, the prefix

must be a DNS subdomain: a series of DNS labels separated by dots (.),

not longer than 253 characters in total, followed by a slash (/).

If the prefix is omitted, the label Key is presumed to be private to the user.

Automated system components (e.g. kube-scheduler, kube-controller-manager,

kube-apiserver, kubectl, or other third-party automation) which add labels

to end-user objects must specify a prefix.

The kubernetes.io/ and k8s.io/ prefixes are

reserved for Kubernetes core components.

Valid label value:

- must be 63 characters or less (can be empty),

- unless empty, must begin and end with an alphanumeric character (

[a-z0-9A-Z]), - could contain dashes (

-), underscores (_), dots (.), and alphanumerics between.

For example, here's a manifest for a Pod that has two labels

environment: production and app: nginx:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: label-demo

labels:

environment: production

app: nginx

spec:

containers:

- name: nginx

image: nginx:1.14.2

ports:

- containerPort: 80

Label selectors

Unlike names and UIDs, labels do not provide uniqueness. In general, we expect many objects to carry the same label(s).

Via a label selector, the client/user can identify a set of objects. The label selector is the core grouping primitive in Kubernetes.

The API currently supports two types of selectors: equality-based and set-based.

A label selector can be made of multiple requirements which are comma-separated.

In the case of multiple requirements, all must be satisfied so the comma separator

acts as a logical AND (&&) operator.

The semantics of empty or non-specified selectors are dependent on the context, and API types that use selectors should document the validity and meaning of them.

Note:

For some API types, such as ReplicaSets, the label selectors of two instances must not overlap within a namespace, or the controller can see that as conflicting instructions and fail to determine how many replicas should be present.Caution:

For both equality-based and set-based conditions there is no logical OR (||) operator.

Ensure your filter statements are structured accordingly.Equality-based requirement

Equality- or inequality-based requirements allow filtering by label keys and values.

Matching objects must satisfy all of the specified label constraints, though they may

have additional labels as well. Three kinds of operators are admitted =,==,!=.

The first two represent equality (and are synonyms), while the latter represents inequality.

For example:

environment = production

tier != frontend

The former selects all resources with key equal to environment and value equal to production.

The latter selects all resources with key equal to tier and value distinct from frontend,

and all resources with no labels with the tier key. One could filter for resources in production

excluding frontend using the comma operator: environment=production,tier!=frontend

One usage scenario for equality-based label requirement is for Pods to specify

node selection criteria. For example, the sample Pod below selects nodes where

the accelerator label exists and is set to nvidia-tesla-p100.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: cuda-test

spec:

containers:

- name: cuda-test

image: "registry.k8s.io/cuda-vector-add:v0.1"

resources:

limits:

nvidia.com/gpu: 1

nodeSelector:

accelerator: nvidia-tesla-p100

Set-based requirement

Set-based label requirements allow filtering keys according to a set of values.

Three kinds of operators are supported: in,notin and exists (only the key identifier).

For example:

environment in (production, qa)

tier notin (frontend, backend)

partition

!partition

- The first example selects all resources with key equal to

environmentand value equal toproductionorqa. - The second example selects all resources with key equal to

tierand values other thanfrontendandbackend, and all resources with no labels with thetierkey. - The third example selects all resources including a label with key

partition; no values are checked. - The fourth example selects all resources without a label with key

partition; no values are checked.

Similarly the comma separator acts as an AND operator. So filtering resources

with a partition key (no matter the value) and with environment different

than qa can be achieved using partition,environment notin (qa).

The set-based label selector is a general form of equality since

environment=production is equivalent to environment in (production);

similarly for != and notin.

Set-based requirements can be mixed with equality-based requirements.

For example: partition in (customerA, customerB),environment!=qa.

API

LIST and WATCH filtering

For list and watch operations, you can specify label selectors to filter the sets of objects returned; you specify the filter using a query parameter. (To learn in detail about watches in Kubernetes, read efficient detection of changes). Both requirements are permitted (presented here as they would appear in a URL query string):

- equality-based requirements:

?labelSelector=environment%3Dproduction,tier%3Dfrontend - set-based requirements:

?labelSelector=environment+in+%28production%2Cqa%29%2Ctier+in+%28frontend%29

Both label selector styles can be used to list or watch resources via a REST client.

For example, targeting apiserver with kubectl and using equality-based one may write:

kubectl get pods -l environment=production,tier=frontend

or using set-based requirements:

kubectl get pods -l 'environment in (production),tier in (frontend)'

As already mentioned set-based requirements are more expressive. For instance, they can implement the OR operator on values:

kubectl get pods -l 'environment in (production, qa)'

or restricting negative matching via notin operator:

kubectl get pods -l 'environment,environment notin (frontend)'

Set references in API objects

Some Kubernetes objects, such as services

and replicationcontrollers,

also use label selectors to specify sets of other resources, such as

pods.

Service and ReplicationController

The set of pods that a service targets is defined with a label selector.

Similarly, the population of pods that a replicationcontroller should

manage is also defined with a label selector.

Label selectors for both objects are defined in json or yaml files using maps,

and only equality-based requirement selectors are supported:

"selector": {

"component" : "redis",

}

or

selector:

component: redis

This selector (respectively in json or yaml format) is equivalent to

component=redis or component in (redis).

Resources that support set-based requirements

Newer resources, such as Job,

Deployment,

ReplicaSet, and

DaemonSet,

support set-based requirements as well.

selector:

matchLabels:

component: redis

matchExpressions:

- { key: tier, operator: In, values: [cache] }

- { key: environment, operator: NotIn, values: [dev] }

matchLabels is a map of {key,value} pairs. A single {key,value} in the

matchLabels map is equivalent to an element of matchExpressions, whose key

field is "key", the operator is "In", and the values array contains only "value".

matchExpressions is a list of pod selector requirements. Valid operators include

In, NotIn, Exists, and DoesNotExist. The values set must be non-empty in the case of

In and NotIn. All of the requirements, from both matchLabels and matchExpressions

are ANDed together -- they must all be satisfied in order to match.

Selecting sets of nodes

One use case for selecting over labels is to constrain the set of nodes onto which a pod can schedule. See the documentation on node selection for more information.

Using labels effectively

You can apply a single label to any resources, but this is not always the best practice. There are many scenarios where multiple labels should be used to distinguish resource sets from one another.

For instance, different applications would use different values for the app label, but a

multi-tier application, such as the guestbook example,

would additionally need to distinguish each tier. The frontend could carry the following labels:

labels:

app: guestbook

tier: frontend

while the Redis master and replica would have different tier labels, and perhaps even an

additional role label:

labels:

app: guestbook

tier: backend

role: master

and

labels:

app: guestbook

tier: backend

role: replica

The labels allow for slicing and dicing the resources along any dimension specified by a label:

kubectl apply -f examples/guestbook/all-in-one/guestbook-all-in-one.yaml

kubectl get pods -Lapp -Ltier -Lrole

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE APP TIER ROLE

guestbook-fe-4nlpb 1/1 Running 0 1m guestbook frontend <none>

guestbook-fe-ght6d 1/1 Running 0 1m guestbook frontend <none>

guestbook-fe-jpy62 1/1 Running 0 1m guestbook frontend <none>

guestbook-redis-master-5pg3b 1/1 Running 0 1m guestbook backend master

guestbook-redis-replica-2q2yf 1/1 Running 0 1m guestbook backend replica

guestbook-redis-replica-qgazl 1/1 Running 0 1m guestbook backend replica

my-nginx-divi2 1/1 Running 0 29m nginx <none> <none>

my-nginx-o0ef1 1/1 Running 0 29m nginx <none> <none>

kubectl get pods -lapp=guestbook,role=replica

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

guestbook-redis-replica-2q2yf 1/1 Running 0 3m

guestbook-redis-replica-qgazl 1/1 Running 0 3m

Updating labels

Sometimes you may want to relabel existing pods and other resources before creating

new resources. This can be done with kubectl label.

For example, if you want to label all your NGINX Pods as frontend tier, run:

kubectl label pods -l app=nginx tier=fe

pod/my-nginx-2035384211-j5fhi labeled

pod/my-nginx-2035384211-u2c7e labeled

pod/my-nginx-2035384211-u3t6x labeled

This first filters all pods with the label "app=nginx", and then labels them with the "tier=fe". To see the pods you labeled, run:

kubectl get pods -l app=nginx -L tier

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE TIER

my-nginx-2035384211-j5fhi 1/1 Running 0 23m fe

my-nginx-2035384211-u2c7e 1/1 Running 0 23m fe

my-nginx-2035384211-u3t6x 1/1 Running 0 23m fe

This outputs all "app=nginx" pods, with an additional label column of pods' tier

(specified with -L or --label-columns).

For more information, please see kubectl label.

What's next

1.2.4 - Namespaces

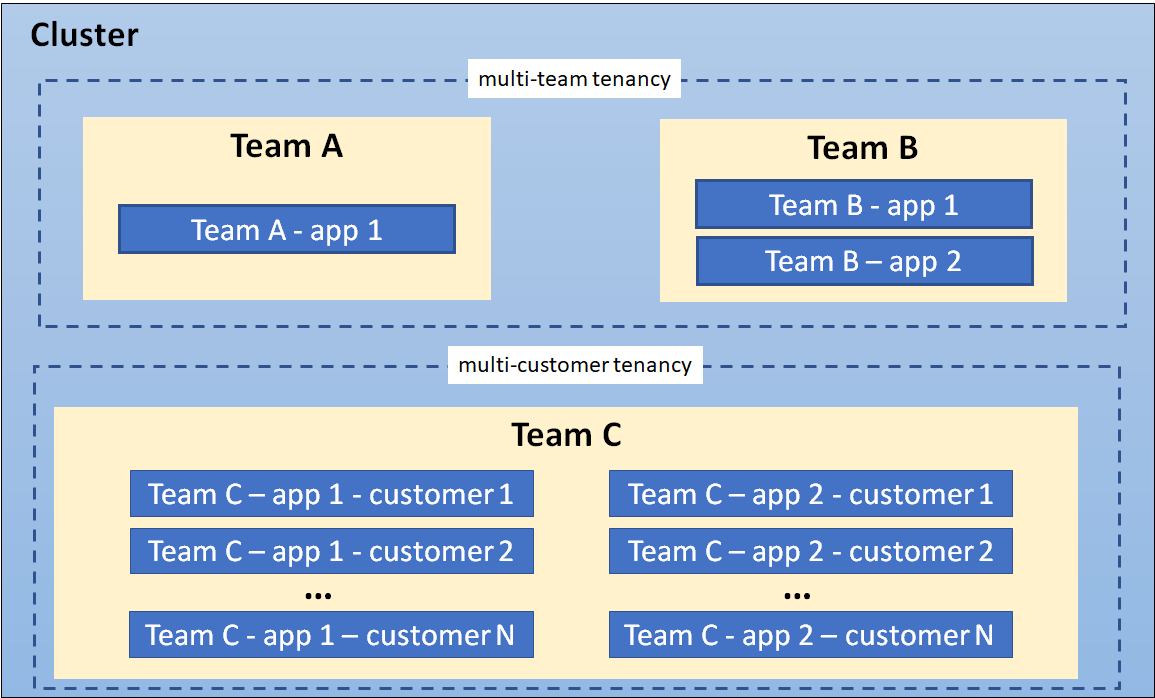

In Kubernetes, namespaces provide a mechanism for isolating groups of resources within a single cluster. Names of resources need to be unique within a namespace, but not across namespaces. Namespace-based scoping is applicable only for namespaced objects (e.g. Deployments, Services, etc.) and not for cluster-wide objects (e.g. StorageClass, Nodes, PersistentVolumes, etc.).

When to Use Multiple Namespaces

Namespaces are intended for use in environments with many users spread across multiple teams, or projects. For clusters with a few to tens of users, you should not need to create or think about namespaces at all. Start using namespaces when you need the features they provide.

Namespaces provide a scope for names. Names of resources need to be unique within a namespace, but not across namespaces. Namespaces cannot be nested inside one another and each Kubernetes resource can only be in one namespace.

Namespaces are a way to divide cluster resources between multiple users (via resource quota).

It is not necessary to use multiple namespaces to separate slightly different resources, such as different versions of the same software: use labels to distinguish resources within the same namespace.

Note:

For a production cluster, consider not using thedefault namespace. Instead, make other namespaces and use those.Initial namespaces

Kubernetes starts with four initial namespaces:

default- Kubernetes includes this namespace so that you can start using your new cluster without first creating a namespace.

kube-node-lease- This namespace holds Lease objects associated with each node. Node leases allow the kubelet to send heartbeats so that the control plane can detect node failure.

kube-public- This namespace is readable by all clients (including those not authenticated). This namespace is mostly reserved for cluster usage, in case that some resources should be visible and readable publicly throughout the whole cluster. The public aspect of this namespace is only a convention, not a requirement.

kube-system- The namespace for objects created by the Kubernetes system.

Working with Namespaces

Creation and deletion of namespaces are described in the Admin Guide documentation for namespaces.

Note:

Avoid creating namespaces with the prefixkube-, since it is reserved for Kubernetes system namespaces.Viewing namespaces

You can list the current namespaces in a cluster using:

kubectl get namespace

NAME STATUS AGE

default Active 1d

kube-node-lease Active 1d

kube-public Active 1d

kube-system Active 1d

Setting the namespace for a request

To set the namespace for a current request, use the --namespace flag.

For example:

kubectl run nginx --image=nginx --namespace=<insert-namespace-name-here>

kubectl get pods --namespace=<insert-namespace-name-here>

Setting the namespace preference

You can permanently save the namespace for all subsequent kubectl commands in that context.

kubectl config set-context --current --namespace=<insert-namespace-name-here>

# Validate it

kubectl config view --minify | grep namespace:

Namespaces and DNS

When you create a Service,

it creates a corresponding DNS entry.

This entry is of the form <service-name>.<namespace-name>.svc.cluster.local, which means

that if a container only uses <service-name>, it will resolve to the service which

is local to a namespace. This is useful for using the same configuration across

multiple namespaces such as Development, Staging and Production. If you want to reach

across namespaces, you need to use the fully qualified domain name (FQDN).

As a result, all namespace names must be valid RFC 1123 DNS labels.

Warning:

By creating namespaces with the same name as public top-level domains, Services in these namespaces can have short DNS names that overlap with public DNS records. Workloads from any namespace performing a DNS lookup without a trailing dot will be redirected to those services, taking precedence over public DNS.

To mitigate this, limit privileges for creating namespaces to trusted users. If required, you could additionally configure third-party security controls, such as admission webhooks, to block creating any namespace with the name of public TLDs.

Not all objects are in a namespace

Most Kubernetes resources (e.g. pods, services, replication controllers, and others) are in some namespaces. However namespace resources are not themselves in a namespace. And low-level resources, such as nodes and persistentVolumes, are not in any namespace.

To see which Kubernetes resources are and aren't in a namespace:

# In a namespace

kubectl api-resources --namespaced=true

# Not in a namespace

kubectl api-resources --namespaced=false

Automatic labelling

Kubernetes 1.22 [stable]The Kubernetes control plane sets an immutable label

kubernetes.io/metadata.name on all namespaces.

The value of the label is the namespace name.

What's next

- Learn more about creating a new namespace.

- Learn more about deleting a namespace.

1.2.5 - Annotations

You can use Kubernetes annotations to attach arbitrary non-identifying metadata to objects. Clients such as tools and libraries can retrieve this metadata.

Attaching metadata to objects

You can use either labels or annotations to attach metadata to Kubernetes objects. Labels can be used to select objects and to find collections of objects that satisfy certain conditions. In contrast, annotations are not used to identify and select objects. The metadata in an annotation can be small or large, structured or unstructured, and can include characters not permitted by labels. It is possible to use labels as well as annotations in the metadata of the same object.

Annotations, like labels, are key/value maps:

"metadata": {

"annotations": {

"key1" : "value1",

"key2" : "value2"

}

}

Note:

The keys and the values in the map must be strings. In other words, you cannot use numeric, boolean, list or other types for either the keys or the values.Here are some examples of information that could be recorded in annotations:

Fields managed by a declarative configuration layer. Attaching these fields as annotations distinguishes them from default values set by clients or servers, and from auto-generated fields and fields set by auto-sizing or auto-scaling systems.

Build, release, or image information like timestamps, release IDs, git branch, PR numbers, image hashes, and registry address.

Pointers to logging, monitoring, analytics, or audit repositories.

Client library or tool information that can be used for debugging purposes: for example, name, version, and build information.

User or tool/system provenance information, such as URLs of related objects from other ecosystem components.

Lightweight rollout tool metadata: for example, config or checkpoints.

Phone or pager numbers of persons responsible, or directory entries that specify where that information can be found, such as a team web site.

Directives from the end-user to the implementations to modify behavior or engage non-standard features.

Instead of using annotations, you could store this type of information in an external database or directory, but that would make it much harder to produce shared client libraries and tools for deployment, management, introspection, and the like.

Syntax and character set

Annotations are key/value pairs. Valid annotation keys have two segments: an optional prefix and name, separated by a slash (/). The name segment is required and must be 63 characters or less, beginning and ending with an alphanumeric character ([a-z0-9A-Z]) with dashes (-), underscores (_), dots (.), and alphanumerics between. The prefix is optional. If specified, the prefix must be a DNS subdomain: a series of DNS labels separated by dots (.), not longer than 253 characters in total, followed by a slash (/).

If the prefix is omitted, the annotation Key is presumed to be private to the user. Automated system components (e.g. kube-scheduler, kube-controller-manager, kube-apiserver, kubectl, or other third-party automation) which add annotations to end-user objects must specify a prefix.

The kubernetes.io/ and k8s.io/ prefixes are reserved for Kubernetes core components.

For example, here's a manifest for a Pod that has the annotation imageregistry: https://hub.docker.com/ :

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: annotations-demo

annotations:

imageregistry: "https://hub.docker.com/"

spec:

containers:

- name: nginx

image: nginx:1.14.2

ports:

- containerPort: 80

What's next

- Learn more about Labels and Selectors.

- Find Well-known labels, Annotations and Taints

1.2.6 - Field Selectors

Field selectors let you select Kubernetes objects based on the value of one or more resource fields. Here are some examples of field selector queries:

metadata.name=my-servicemetadata.namespace!=defaultstatus.phase=Pending

This kubectl command selects all Pods for which the value of the status.phase field is Running:

kubectl get pods --field-selector status.phase=Running

Note:

Field selectors are essentially resource filters. By default, no selectors/filters are applied, meaning that all resources of the specified type are selected. This makes thekubectl queries kubectl get pods and kubectl get pods --field-selector "" equivalent.Supported fields

Supported field selectors vary by Kubernetes resource type. All resource types support the metadata.name and metadata.namespace fields. Using unsupported field selectors produces an error. For example:

kubectl get ingress --field-selector foo.bar=baz

Error from server (BadRequest): Unable to find "ingresses" that match label selector "", field selector "foo.bar=baz": "foo.bar" is not a known field selector: only "metadata.name", "metadata.namespace"

List of supported fields

| Kind | Fields |

|---|---|

| Pod | spec.nodeNamespec.restartPolicyspec.schedulerNamespec.serviceAccountNamespec.hostNetworkstatus.phasestatus.podIPstatus.podIPsstatus.nominatedNodeName |

| Event | involvedObject.kindinvolvedObject.namespaceinvolvedObject.nameinvolvedObject.uidinvolvedObject.apiVersioninvolvedObject.resourceVersioninvolvedObject.fieldPathreasonreportingComponentsourcetype |

| Secret | type |

| Namespace | status.phase |

| ReplicaSet | status.replicas |

| ReplicationController | status.replicas |

| Job | status.successful |

| Node | spec.unschedulable |

| CertificateSigningRequest | spec.signerName |

Custom resources fields

All custom resource types support the metadata.name and metadata.namespace fields.

Additionally, the spec.versions[*].selectableFields field of a CustomResourceDefinition

declares which other fields in a custom resource may be used in field selectors. See selectable fields for custom resources

for more information about how to use field selectors with CustomResourceDefinitions.

Supported operators

You can use the =, ==, and != operators with field selectors (= and == mean the same thing). This kubectl command, for example, selects all Kubernetes Services that aren't in the default namespace:

kubectl get services --all-namespaces --field-selector metadata.namespace!=default

Chained selectors

As with label and other selectors, field selectors can be chained together as a comma-separated list. This kubectl command selects all Pods for which the status.phase does not equal Running and the spec.restartPolicy field equals Always:

kubectl get pods --field-selector=status.phase!=Running,spec.restartPolicy=Always

Multiple resource types

You can use field selectors across multiple resource types. This kubectl command selects all Statefulsets and Services that are not in the default namespace:

kubectl get statefulsets,services --all-namespaces --field-selector metadata.namespace!=default

1.2.7 - Finalizers

Finalizers are namespaced keys that tell Kubernetes to wait until specific conditions are met before it fully deletes resources that are marked for deletion. Finalizers alert controllers to clean up resources the deleted object owned.

When you tell Kubernetes to delete an object that has finalizers specified for

it, the Kubernetes API marks the object for deletion by populating .metadata.deletionTimestamp,

and returns a 202 status code (HTTP "Accepted"). The target object remains in a terminating state while the

control plane, or other components, take the actions defined by the finalizers.

After these actions are complete, the controller removes the relevant finalizers

from the target object. When the metadata.finalizers field is empty,

Kubernetes considers the deletion complete and deletes the object.

You can use finalizers to control garbage collection of resources. For example, you can define a finalizer to clean up related API resources or infrastructure before the controller deletes the object being finalized.

You can use finalizers to control garbage collection of objects by alerting controllers to perform specific cleanup tasks before deleting the target resource.

Finalizers don't usually specify the code to execute. Instead, they are typically lists of keys on a specific resource similar to annotations. Kubernetes specifies some finalizers automatically, but you can also specify your own.

How finalizers work

When you create a resource using a manifest file, you can specify finalizers in

the metadata.finalizers field. When you attempt to delete the resource, the

API server handling the delete request notices the values in the finalizers field

and does the following:

- Modifies the object to add a

metadata.deletionTimestampfield with the time you started the deletion. - Prevents the object from being removed until all items are removed from its

metadata.finalizersfield - Returns a

202status code (HTTP "Accepted")

The controller managing that finalizer notices the update to the object setting the

metadata.deletionTimestamp, indicating deletion of the object has been requested.

The controller then attempts to satisfy the requirements of the finalizers

specified for that resource. Each time a finalizer condition is satisfied, the

controller removes that key from the resource's finalizers field. When the

finalizers field is emptied, an object with a deletionTimestamp field set

is automatically deleted. You can also use finalizers to prevent deletion of unmanaged resources.

A common example of a finalizer is kubernetes.io/pv-protection, which prevents

accidental deletion of PersistentVolume objects. When a PersistentVolume

object is in use by a Pod, Kubernetes adds the pv-protection finalizer. If you

try to delete the PersistentVolume, it enters a Terminating status, but the

controller can't delete it because the finalizer exists. When the Pod stops

using the PersistentVolume, Kubernetes clears the pv-protection finalizer,

and the controller deletes the volume.

Note:

When you

DELETEan object, Kubernetes adds the deletion timestamp for that object and then immediately starts to restrict changes to the.metadata.finalizersfield for the object that is now pending deletion. You can remove existing finalizers (deleting an entry from thefinalizerslist) but you cannot add a new finalizer. You also cannot modify thedeletionTimestampfor an object once it is set.After the deletion is requested, you can not resurrect this object. The only way is to delete it and make a new similar object.

Note:

Custom finalizer names must be publicly qualified finalizer names, such asexample.com/finalizer-name.

Kubernetes enforces this format; the API server rejects writes to objects where the change does not use qualified finalizer names for any custom finalizer.Owner references, labels, and finalizers

Like labels, owner references describe the relationships between objects in Kubernetes, but are used for a different purpose. When a controller manages objects like Pods, it uses labels to track changes to groups of related objects. For example, when a Job creates one or more Pods, the Job controller applies labels to those pods and tracks changes to any Pods in the cluster with the same label.

The Job controller also adds owner references to those Pods, pointing at the Job that created the Pods. If you delete the Job while these Pods are running, Kubernetes uses the owner references (not labels) to determine which Pods in the cluster need cleanup.

Kubernetes also processes finalizers when it identifies owner references on a resource targeted for deletion.

In some situations, finalizers can block the deletion of dependent objects, which can cause the targeted owner object to remain for longer than expected without being fully deleted. In these situations, you should check finalizers and owner references on the target owner and dependent objects to troubleshoot the cause.

Note:

In cases where objects are stuck in a deleting state, avoid manually removing finalizers to allow deletion to continue. Finalizers are usually added to resources for a reason, so forcefully removing them can lead to issues in your cluster. This should only be done when the purpose of the finalizer is understood and is accomplished in another way (for example, manually cleaning up some dependent object).What's next

- Read Using Finalizers to Control Deletion on the Kubernetes blog.

1.2.8 - Owners and Dependents

In Kubernetes, some objects are owners of other objects. For example, a ReplicaSet is the owner of a set of Pods. These owned objects are dependents of their owner.

Ownership is different from the labels and selectors

mechanism that some resources also use. For example, consider a Service that

creates EndpointSlice objects. The Service uses labels to allow the control plane to

determine which EndpointSlice objects are used for that Service. In addition

to the labels, each EndpointSlice that is managed on behalf of a Service has

an owner reference. Owner references help different parts of Kubernetes avoid

interfering with objects they don’t control.

Owner references in object specifications

Dependent objects have a metadata.ownerReferences field that references their

owner object. A valid owner reference consists of the object name and a UID

within the same namespace as the dependent object. Kubernetes sets the value of

this field automatically for objects that are dependents of other objects like

ReplicaSets, DaemonSets, Deployments, Jobs and CronJobs, and ReplicationControllers.

You can also configure these relationships manually by changing the value of

this field. However, you usually don't need to and can allow Kubernetes to

automatically manage the relationships.

Dependent objects also have an ownerReferences.blockOwnerDeletion field that

takes a boolean value and controls whether specific dependents can block garbage

collection from deleting their owner object. Kubernetes automatically sets this

field to true if a controller

(for example, the Deployment controller) sets the value of the

metadata.ownerReferences field. You can also set the value of the

blockOwnerDeletion field manually to control which dependents block garbage

collection.

A Kubernetes admission controller controls user access to change this field for dependent resources, based on the delete permissions of the owner. This control prevents unauthorized users from delaying owner object deletion.

Note:

Cross-namespace owner references are disallowed by design. Namespaced dependents can specify cluster-scoped or namespaced owners. A namespaced owner must exist in the same namespace as the dependent. If it does not, the owner reference is treated as absent, and the dependent is subject to deletion once all owners are verified absent.

Cluster-scoped dependents can only specify cluster-scoped owners. In v1.20+, if a cluster-scoped dependent specifies a namespaced kind as an owner, it is treated as having an unresolvable owner reference, and is not able to be garbage collected.

In v1.20+, if the garbage collector detects an invalid cross-namespace ownerReference,

or a cluster-scoped dependent with an ownerReference referencing a namespaced kind, a warning Event

with a reason of OwnerRefInvalidNamespace and an involvedObject of the invalid dependent is reported.

You can check for that kind of Event by running

kubectl get events -A --field-selector=reason=OwnerRefInvalidNamespace.

Ownership and finalizers

When you tell Kubernetes to delete a resource, the API server allows the

managing controller to process any finalizer rules

for the resource. Finalizers

prevent accidental deletion of resources your cluster may still need to function

correctly. For example, if you try to delete a PersistentVolume that is still

in use by a Pod, the deletion does not happen immediately because the

PersistentVolume has the kubernetes.io/pv-protection finalizer on it.

Instead, the volume remains in the Terminating status until Kubernetes clears

the finalizer, which only happens after the PersistentVolume is no longer

bound to a Pod.

Kubernetes also adds finalizers to an owner resource when you use either

foreground or orphan cascading deletion.

In foreground deletion, it adds the foreground finalizer so that the

controller must delete dependent resources that also have

ownerReferences.blockOwnerDeletion=true before it deletes the owner. If you

specify an orphan deletion policy, Kubernetes adds the orphan finalizer so

that the controller ignores dependent resources after it deletes the owner

object.

What's next

- Learn more about Kubernetes finalizers.

- Learn about garbage collection.

- Read the API reference for object metadata.

1.2.9 - Recommended Labels

You can visualize and manage Kubernetes objects with more tools than kubectl and the dashboard. A common set of labels allows tools to work interoperably, describing objects in a common manner that all tools can understand.

In addition to supporting tooling, the recommended labels describe applications in a way that can be queried.

The metadata is organized around the concept of an application. Kubernetes is not a platform as a service (PaaS) and doesn't have or enforce a formal notion of an application. Instead, applications are informal and described with metadata. The definition of what an application contains is loose.

Note:

These are recommended labels. They make it easier to manage applications but aren't required for any core tooling.Shared labels and annotations share a common prefix: app.kubernetes.io. Labels

without a prefix are private to users. The shared prefix ensures that shared labels

do not interfere with custom user labels.

Labels

In order to take full advantage of using these labels, they should be applied on every resource object.

| Key | Description | Example | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

app.kubernetes.io/name | The name of the application | mysql | string |

app.kubernetes.io/instance | A unique name identifying the instance of an application | mysql-abcxyz | string |

app.kubernetes.io/version | The current version of the application (e.g., a SemVer 1.0, revision hash, etc.) | 5.7.21 | string |

app.kubernetes.io/component | The component within the architecture | database | string |

app.kubernetes.io/part-of | The name of a higher level application this one is part of | wordpress | string |

app.kubernetes.io/managed-by | The tool being used to manage the operation of an application | Helm | string |

To illustrate these labels in action, consider the following StatefulSet object:

# This is an excerpt

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: StatefulSet

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: mysql

app.kubernetes.io/instance: mysql-abcxyz

app.kubernetes.io/version: "5.7.21"

app.kubernetes.io/component: database

app.kubernetes.io/part-of: wordpress

app.kubernetes.io/managed-by: Helm

Applications And Instances Of Applications

An application can be installed one or more times into a Kubernetes cluster and, in some cases, the same namespace. For example, WordPress can be installed more than once where different websites are different installations of WordPress.

The name of an application and the instance name are recorded separately. For

example, WordPress has a app.kubernetes.io/name of wordpress while it has

an instance name, represented as app.kubernetes.io/instance with a value of

wordpress-abcxyz. This enables the application and instance of the application

to be identifiable. Every instance of an application must have a unique name.

Examples

To illustrate different ways to use these labels the following examples have varying complexity.

A Simple Stateless Service

Consider the case for a simple stateless service deployed using Deployment and Service objects. The following two snippets represent how the labels could be used in their simplest form.

The Deployment is used to oversee the pods running the application itself.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: myservice

app.kubernetes.io/instance: myservice-abcxyz

...

The Service is used to expose the application.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: myservice

app.kubernetes.io/instance: myservice-abcxyz

...

Web Application With A Database

Consider a slightly more complicated application: a web application (WordPress) using a database (MySQL), installed using Helm. The following snippets illustrate the start of objects used to deploy this application.

The start to the following Deployment is used for WordPress:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: wordpress

app.kubernetes.io/instance: wordpress-abcxyz

app.kubernetes.io/version: "4.9.4"

app.kubernetes.io/managed-by: Helm

app.kubernetes.io/component: server

app.kubernetes.io/part-of: wordpress

...

The Service is used to expose WordPress:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: wordpress

app.kubernetes.io/instance: wordpress-abcxyz

app.kubernetes.io/version: "4.9.4"

app.kubernetes.io/managed-by: Helm

app.kubernetes.io/component: server

app.kubernetes.io/part-of: wordpress

...

MySQL is exposed as a StatefulSet with metadata for both it and the larger application it belongs to:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: StatefulSet

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: mysql

app.kubernetes.io/instance: mysql-abcxyz

app.kubernetes.io/version: "5.7.21"

app.kubernetes.io/managed-by: Helm

app.kubernetes.io/component: database

app.kubernetes.io/part-of: wordpress

...

The Service is used to expose MySQL as part of WordPress:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: mysql

app.kubernetes.io/instance: mysql-abcxyz

app.kubernetes.io/version: "5.7.21"

app.kubernetes.io/managed-by: Helm

app.kubernetes.io/component: database

app.kubernetes.io/part-of: wordpress

...

With the MySQL StatefulSet and Service you'll notice information about both MySQL and WordPress, the broader application, are included.

1.2.10 - Storage Versions

The Kubernetes API server stores objects, relying on an etcd-compatible backing store (often, the backing storage is etcd itself). Each object is serialized using a particular version of that API type; for example, the v1 representation of a ConfigMap. Kubernetes uses the term storage version to describe how an object is stored in your cluster.

The Kubernetes API also relies on automatic conversion; for example, if you have a HorizontalPodAutoscaler, then you can interact with that HorizontalPodAutoscaler using any mix of the v1 and v2 versions of the HorizontalPodAutoscaler API. Kubernetes is responsible for converting each API call so that clients do not see what version is actually serialized.